Automation, loneliness and AI in modern Japan

Ichiran Ramen is one of many automated noodle restaurants in Japan that eliminates the need for human interaction. But is this a good thing? Crystal Lin reports

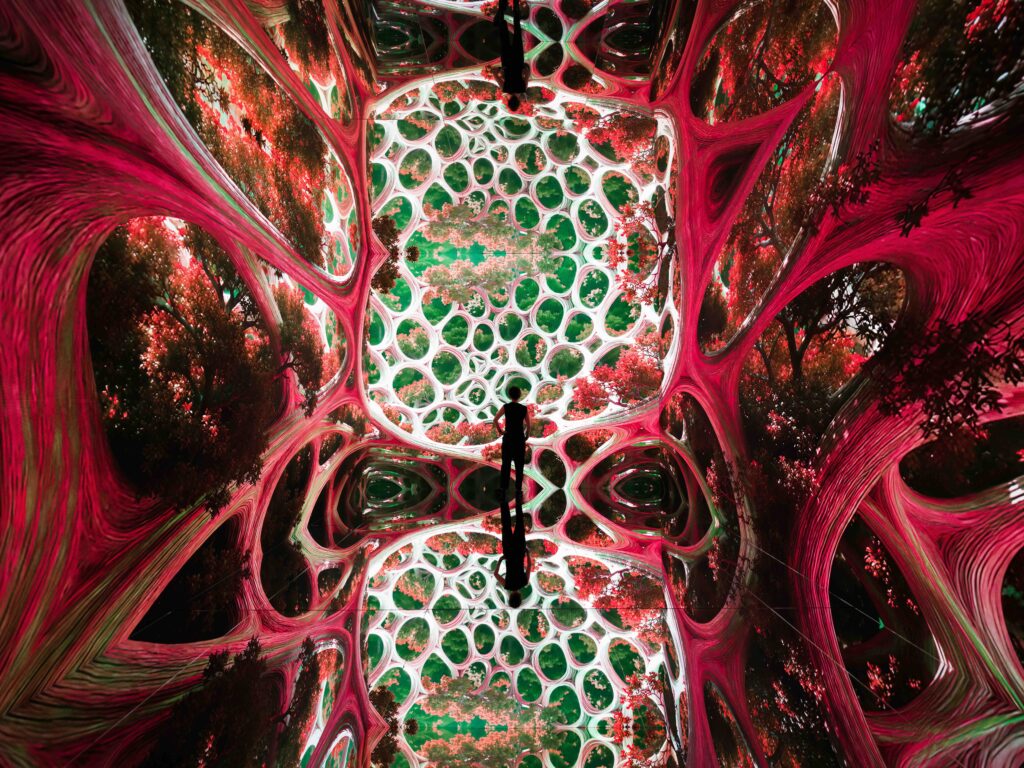

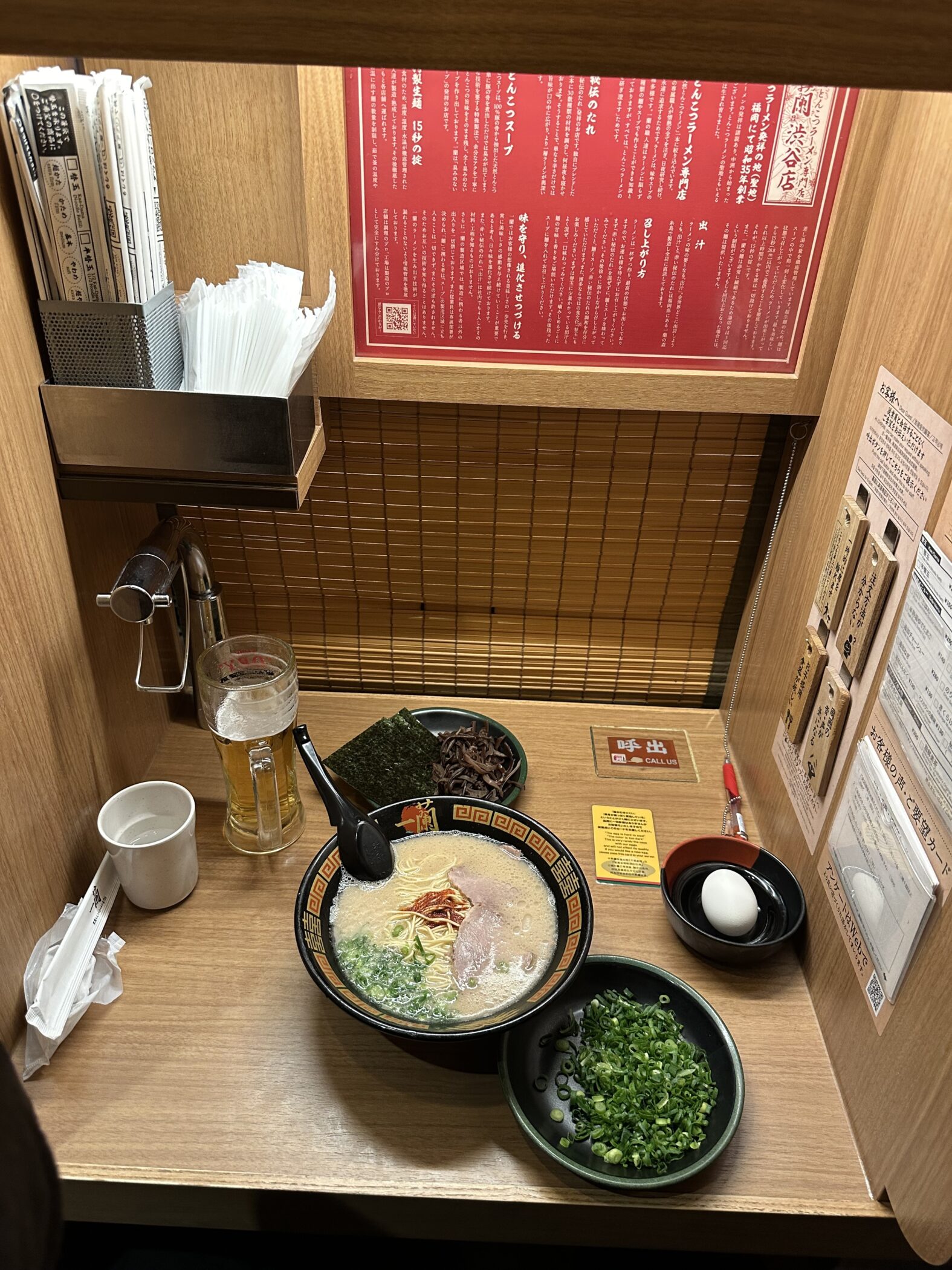

Dining at Ichiran, Japan’s popular automated ramen restaurant, is an impressive, if eerie, experience, in which painstaking efforts have been made to keep human interaction to an absolute minimum.

Upon entering the restaurant, you are greeted with what appear to be ramen vending machines. Ordering is straightforward. Press the button with the photo of your ramen of choice, insert cash or card, and the machine spits out a ticket with your dish number.

Once you have your ticket, you enter the restaurant and survey the electronic seating map, where individual booths are lit red if occupied and green if empty, in a similar fashion to parking garages. You then silently sit down in a small wooden cubicle; dividers block you from the next diner.

A pull-down bamboo screen in front of you then lifts, and a hand – a human one, at least for now – emerges to take your ticket. Within minutes the hand returns with a piping hot bowl of ramen, made to the specifications you selected in the vending machine. Noodle firmness, broth richness, and add-on toppings are all custom options.

Small wooden signs with common requests and complaints hang on either side of the booth – there is no need to speak to the server in case of an issue. One little card says “It’s too noisy” in several different languages. Another can alert the server that you plan to leave your seat for a moment, so that the server can prevent your seat sensor from making your seat appear available in the electronic seating map.

Ichiran’s process is especially designed to eliminate the need for human interaction, and the chain is not alone in its efforts to automate the dining experience. Sushiro, another popular chain restaurant known for conveyor belt sushi, bypasses the need for staff via a network of conveyer belts that operate similarly to train tracks – customers order on a tablet, and your order is shipped from the kitchen and diverted directly to your table. Your tablet announces that your order is ready and to remove it from the conveyer belt. From start to finish, customers need not interact with another human.

Sushiro, another popular chain restaurant known for conveyor belt sushi, bypasses the need for staff via a network of conveyer belts that operate similarly to train tracks – customers order on a tablet, and your order is shipped from the kitchen and diverted directly to your table. Your tablet announces that your order is ready and to remove it from the conveyer belt. From start to finish, customers need not interact with another human.

This efficient yet jarring blend of tradition and technology is a hallmark of daily life in modern Japan, where even traditional izakayas use tablets for ordering food.

A hotel called the Henn na – staffed by humanoid robots, along with an anthropomorphic dinosaur bellhop – opened in 2015, although half the robot staff were "fired" due to poor performance in 2019. Once the robots were reprogrammed, it subsequently opened properties in Seoul (South Korea) and New York (both in 2021). Overall it now has about 20 robot hotels in Japan.

Japan has a long history of using technology to automate daily life – the country has the highest ratio of vending machines per capita in the world (there are about 4.1 million of them), at one machine per 23 people. The country’s emphasis on efficiency and precision, especially in the face of an aging population and shrinking labor force, has spilled over into other aspects of life that initially seemed less suitable for automation. While Ichiran, Sushiro, and other similar venues are ostensibly designed for solitude, they are products of a society in which social isolation and loneliness run rampant. In 2021, the Japanese government even appointed a minister of loneliness and isolation. By some estimates, there are 1.5 million hikikomori, social recluses who refuse to go to school or work, living in Japan.

While Ichiran, Sushiro, and other similar venues are ostensibly designed for solitude, they are products of a society in which social isolation and loneliness run rampant. In 2021, the Japanese government even appointed a minister of loneliness and isolation. By some estimates, there are 1.5 million hikikomori, social recluses who refuse to go to school or work, living in Japan.

Businesses that cater to those living in solitude capitalize on the rising epidemic of social isolation in Japan. The combination of rising loneliness and advanced technology has spawned a variety of creative industries that seek to commodify and replicate human connection.

The advent of AI has given businesses such as these powerful new ways to cater to customers’ every demand.

Gatebox is a company that provides a tiny holographic home assistant – her name is Azuma and she costs around US$2,300 – that operates like a loving housewife, reminding her owner to “come home early” and “pack an umbrella”. She lives inside a glass container outfitted with sensors that can detect her owner’s facial expressions and is able to respond to conversation in a natural way.

A commercial for Gatebox features a young salaryman gazing up at his apartment building, where Azuma has already turned on the lights for his arrival. “Finally,” he smiles to himself, “there is someone waiting for me at home.”

The more Azuma’s owner interacts with her, the more she learns about his habits and movements throughout the day. Gatebox is now developing its technology in conjunction with ChatGPT.

Much of modern life has already been outsourced to digital technologies, and while this has increased quality of life in Japan and elsewhere, the country’s social woes appear to be both a cause and consequence of an increasing reliance on automation and technology.

A future in which AI powers the commodification of human relationships – in Japan and the rest of the world – is now all too easy to imagine.